Pain Relief and the Unexpected Kung Fu Connection

By PainFix co-founder Yen Tse Yap

Published March 04, 2021

Today, when we think of new drug development, it’s a good bet that we don’t think of kungfu fighters. Pharmaceutical advances happen in the domain of scientists in lab coats. Martial arts, on the other hand, has become associated with wholesome after-school activities for our children or action movies from Hollywood and Hong Kong. Yet, about 2,000 years ago, these two domains were not so clearly separate. Medical innovation to relieve bodily injuries somehow developed within the martial arts community in China.

For most of us, this connection seems quite curious. I’ve been trying to find a definitive explanation for why pain medicine and kung fu were connected in ancient China but no one seems to have an explanation for these two disciplines working together. Nonetheless, there have always been traditional healers among the martial arts community in China.

My grandfather was a recent and personal example. He was a grandmaster in Northern Shaolin Kung Fu and a member of the Chin Woo Martial Arts Association in China that sent him and others to Southeast Asia to share Chinese culture, including martial arts. He was also a healer who inherited knowledge and herbal formulas to treat injuries you would typically find in ardent kung fu practitioners — bruises, cuts, sprains and other types of physical trauma.

My grandfather established a small healing practice at the sports stadium where his martial arts association was housed. His professional life was a mix of teaching kung fu and healing injuries, quite typical of the grandmaster-healers of a more ancient past. He tended to a variety of musculoskeletal injuries, treating conditions that conventional medicine found hard to resolve.

Although he learned the basics of human anatomy and body mechanics through experience and training, it was the traditional Chinese medicine formulas that he inherited from his martial arts forebears that helped him produce life-changing results for his patients. For over five decades, he massaged his patients, cooked his herbal mixture and spread it into a handmade patch, and applied this age-old medicine onto bruises, inflamed joints, sprains and strains. While the original healers used the medicines on patients who fought to defend their villages or clans from foreign incursions, my grandfather used them on newer problems that began to affect the human body ever since humans started settling into sedentary lives.

Researchers who study innovation processes are no strangers to the idea that the most fertile ground for breakthroughs is at the intersection of different disciplines. History is replete with polymathic inventors and thinkers like Aristotle, Leonardo Da Vinci, Benjamin Franklin and Nikola Tesla. One of the greatest innovators of our time, Steve Jobs himself said,

“It is in Apple’s DNA that technology alone is not enough — it’s technology married with liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields us the results that make our heart sing.”

People exposed to different subject matters have at their disposal a broader set of mental models and tools to solve any problem. When faced with unfamiliar situations, they use tools like analogues from areas they are familiar with to imagine how a process might work. A famous exponent of analogical thinking is Johannes Kepler, a 16th century German astronomer who unravelled the mystery of planetary motion.

In the world of the living, Charles Darwin is perhaps one of history’s greatest examples of an individual who blended ideas and experiences from his wide-ranging interests to produce arguably our greatest scientific discovery. His breakthrough came when he read the work of economist Thomas Malthus, who argued that humanity was destined to struggle for existence because population growth would increase faster than the growth of its food supply. Darwin analogized this to organisms in the natural world who must also compete for scarce resources in their struggle to survive.

He observed that individual organisms vary ever so slightly, and those with variations that gave them an advantage in their environment were ‘selected’ by nature to better survive and reproduce. Darwin’s training in geology also gave him an appreciation of the depth of geological time, and how incremental but cumulative changes can produce mind-bending changes such as the rise of the Andes or indeed, the rich biodiversity of life.

In his book Range, Why Generalists Triumph In A Specialized World, David Epstein tells the story of psychologist Kevin Dunbar, who studied how world-class molecular biology labs worked. He observed that labs with scientists from more diverse professional backgrounds produced more breakthrough findings.

In one notable example, two labs faced the same experimental problem at around the same time. One lab consisted of only E.coli experts while the other had medical students and scientists with chemistry, physics, biology and genetics backgrounds. Scientists in the first lab used only E.coli knowledge to deal with the problem and took weeks to solve it. The other lab, on the other hand, drew on the medical background of some of its participants and solved the problem in one meeting.

In another example from the field of medicine, one of the most important medical discoveries of the 20th century occurred when the worlds of modern science and traditional medicine collided. During the Vietnam War, Chairman Mao Zedong commissioned Project 523 to find a cure for malaria. The disease was causing enormous casualties among North Vietnamese soldiers, who turned to China for help. By this time, scientists all over the world had tested more than 240,000 compounds for use in antimalarial drugs, but none had worked.

A pharmacologist without a medical degree or doctorate, Tu Youyou, was appointed to head Project 523 in 1967. Her team scoured ancient traditional Chinese medicine texts and eventually discovered a reference to an herb called sweet wormwood, which had been used in China around 400 AD to treat “intermittent fevers”, a symptom of malaria. After testing the herb’s efficacy, they distilled its active ingredient, artemisinin in 1971. Between 2000 and 2015, artemisinin-based therapies helped avert 146 million cases of malaria in Africa alone. This discovery has been called “the most important pharmaceutical intervention in the last half-century”. Tu went on to win the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2015.

It’s not unusual, therefore, to see new ideas and inventions emerge when we blend cultures and ideas. So perhaps when martial arts and traditional medicine came together hundreds of years ago in China, they didn’t make such strange bedfellows after all. It’s only through our 21st century lenses that we see kung fu and medicinal herbs as incongruous bedmates. In times of yore, these fields overlapped more naturally and produced some highly valuable knowledge about how to manage physical pain.

Speculating on why these two fields came together is easier than speculating on how it happened. When Chinese martial arts started institutionalizing in places like the Shaolin Temple, kung fu students lived and trained within those grounds. It doesn’t take a big leap to imagine that bruised or broken disciples would seek out solutions from the masters or healers within the grounds of the institution, and they in turn, would have a set of available remedies to treat their disciples.

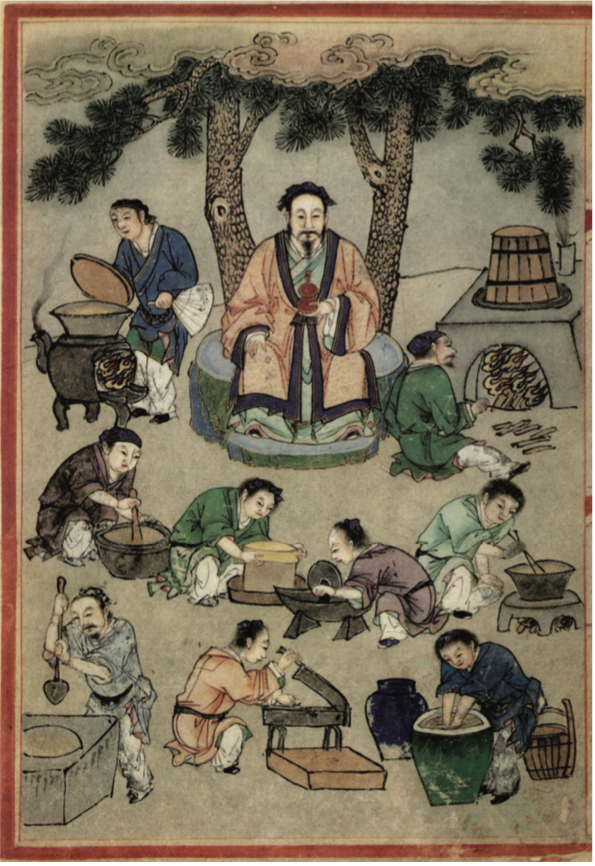

How these medicine men discovered their unique remedies is a trickier question. Perhaps this started with earlier healers who built on simpler herbal remedies that were widely known in the community. This was an era where Chinese healers experimented heavily from the natural world, combining herbs, plants and animal byproducts together to treat different ailments. This approach or “best practice” of trial and error combinations from nature could have been shared between healers of the day and then adopted in a more focused manner by kung fu healers for problems that were more prevalent in their world, such as blunt force trauma from punches or kicks, broken bones, ligament sprains and muscle strains.

When diverse knowledge and experiences blend, problems can be attacked with a wider range of tools. I believe that the kung fu communities in ancient China became fruitful grounds for studying body mechanics and experimenting with new pain relief formulas because the healers combined general pharmacological knowledge with more specialized approaches and ingredients to address their community-specific symptoms. While the village doctor was concerned with general maladies such as fevers, colds or diarrhea, the healers in kung fu communities focused on a smaller subset of problems, of a musculoskeletal nature.

The arc of medical innovation in pain relief over the next 1,000 years has been a short one in the West. Modern painkillers are the offspring of discoveries made hundreds of years ago. Aspirin pills are a distillery away from the willow bark Hippocrates prescribed to the ancient Greeks, and modern opioid drugs are more powerful versions of opiates derived from poppies, called the “joy plant” by the Sumerians 5,000 years ago. Even physical therapy is not a modern invention. Manual therapy, massage and movement were used for treatment by the ancient Greeks and Chinese.

A small community within China pursued a different paradigm however. For centuries, through trial and error, the healers in the kung fu communities refined their formulas, guarded these secrets and only handed them down to their best disciples. When China started to industrialize and urbanize in the 19th century, modern doctors replaced traditional healers, leaving only a small circle of people privy to the medical knowledge that the kung fu communities developed over generations.

That knowledge holds valuable insights for how we will approach pain relief in the 21st century.

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. The information contained herein is not a substitute for and should never be relied upon for professional medical advice. Always talk to your doctor about the risks and benefits of any treatment.